As digital technologies reshape language classrooms worldwide, a key question arises: how can we ensure these tools genuinely support learning rather than distract from it? One powerful answer lies in the theory of embodied cognition, which posits that the mind is not separate from the body, but deeply interconnected with it. In this view, language learning is more effective when learners are physically and emotionally engaged—not just mentally active.

This perspective has powerful implications, especially when paired with innovations like Robot-Assisted Language Learning (RALL). In non-native speaking countries, where English is a compulsory foreign language but student engagement remains a challenge, RALL has the potential to make language learning more tangible, interactive, and inclusive.

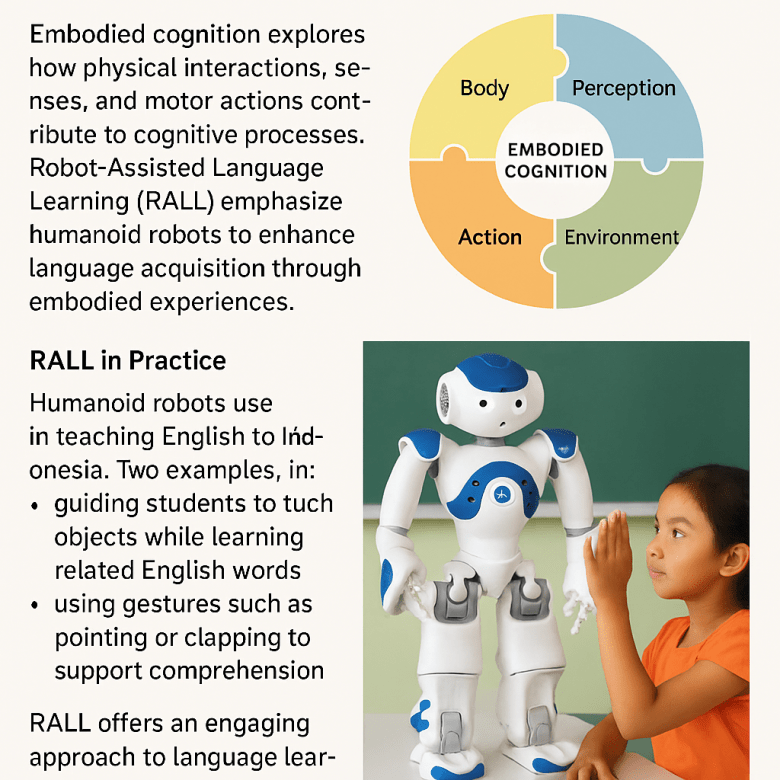

What is Embodied Cognition in Language Learning?

Embodied cognition emphasizes that cognition is rooted in bodily experience and sensorimotor interaction (Barsalou, 2008; Glenberg & Gallese, 2012). In second language acquisition (SLA), this means that gestures, movement, and the physical environment can enhance language comprehension and retention (Macedonia, 2014).

For instance, when learners act out verbs (e.g., “jump” by actually jumping) or associate spatial movement with prepositions (“in,” “on,” “under”), their learning becomes embodied, and therefore more deeply encoded in memory (Hostetter & Alibali, 2008).

Robot-Assisted Language Learning (RALL): A Natural Fit

RALL uses humanoid robots—robots with human-like features and movement—to support language instruction. These robots are not just machines delivering lessons; they interact using speech, movement, and social cues, creating a multisensory, embodied learning environment.

Key benefits of RALL include:

- Interactive vocabulary acquisition with pointing and object manipulation (Belpaeme et al., 2018).

- Turn-taking and conversational practice to improve speaking fluency (Kory-Westlund & Breazeal, 2019).

- Emotional and social engagement, particularly effective with shy or anxious learners (Vogt et al., 2019).

- Multimodal input, including gestures and facial expressions, supporting inclusive learning (Vogt & van den Berghe, 2019).

RALL in Non-Native English Context: Real Possibilities

In non-native English country, like Indonesia, English is taught in primary through tertiary education, yet many students lack speaking confidence and real-world application skills. RALL offers a hands-on, engaging supplement to textbook-based instruction, especially in urban and pilot smart schools or inclusive classrooms.

Example Use Cases:

- Vocabulary with Real Objects and Commands

A humanoid robot like NAO or Kebbi can direct students: “Touch the apple,” “Point to the red book.” This blends physical action with vocabulary practice, aligning with embodied cognition (Macedonia & Knösche, 2011). - Grammar Practice with Gestures

Robots gesture while saying sentences:

“I am running” (robot points to itself),

“You are reading” (points to student), reinforcing pronoun-verb structures through physical mapping. - Speaking Confidence and Turn-Taking

In speaking tasks, robots offer predictable, non-judgmental feedback, reducing affective filters (Kory-Westlund & Breazeal, 2019). Indonesian students often hesitate to speak up in class—robots create a low-pressure speaking partner. - Support in Inclusive Classrooms

Robots with visual displays and motion cues help deaf or neurodiverse learners by pairing gestures and signs with speech, supporting universal design for learning (UDL) principles (Mubin et al., 2013).

A Framework for Embodied Language Learning with Robots

We can summarize the embodied approach in RALL through this framework:

Perception – Action – Language – Context

- Perception: Learners see, hear, and feel through multiple modes.

- Action: Learners act (point, move, repeat, touch) in response.

- Language: Learners link movement with words and structures.

- Context: Learning occurs in meaningful, real-life settings.

This aligns with Glenberg’s (2010) “symbol grounding” principle: words are best learned when tied to sensorimotor experience.

Conclusion and Future Outlook

Embodied cognition reminds us that language is not learned in the abstract—it is grounded in movement, interaction, and lived experience. Robot-Assisted Language Learning brings this idea to life by making English learning conversational, playful, and physical.

For a non-native English country like Indonesia, investing in RALL—starting in teacher training colleges, STEM-integrated schools, and inclusive education pilot programs—could boost learner engagement and support diverse learners in ways traditional methods cannot.

As research and technology advance, combining embodied cognition with social robots may mark a turning point for how we teach English—not just in Indonesia, but globally.

Further Reading

- Barsalou, L. W. (2008). Grounded cognition. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 617–645.

- Belpaeme, T., Kennedy, J., Ramachandran, A., Scassellati, B., & Tanaka, F. (2018). Social robots for education: A review. Science Robotics, 3(21).

- Glenberg, A. M. (2010). Embodiment as a unifying perspective for psychology. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 1(4), 586–596.

- Glenberg, A. M., & Gallese, V. (2012). Action-based language: A theory of language acquisition, comprehension, and production. Cortex, 48(7), 905–922.

- Hostetter, A. B., & Alibali, M. W. (2008). Visible embodiment: Gestures as simulated action. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 15(3), 495–514.

- Kory-Westlund, J. M., & Breazeal, C. (2019). A long-term study of young children’s rapport, social emulation, and language learning with a peer-like robot playmate in preschool. Frontiers in Robotics and AI, 6, 81.

- Macedonia, M. (2014). Bringing back the body into the mind: gestures enhance word learning in foreign language. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1467.

- Macedonia, M., & Knösche, T. R. (2011). Body in mind: How gestures empower foreign language learning. Mind, Brain, and Education, 5(4), 196–211.

- Mubin, O., Stevens, C. J., Shahid, S., Mahmud, A. A., & Dong, J. J. (2013). A review of the applicability of robots in education. Technology for Education and Learning, 1(1).

- Vogt, P., de Haas, M., de Jong, C., Baxter, P., & Krahmer, E. (2019). Child-robot interactions in primary education: A review of the evidence. International Journal of Social Robotics, 11(3), 325–344.

@mhsantosa (2025)